What to Know About the ‘FLiRT’ Variants of COVID-19

The COVID-19 lull in the U.S. may soon come to an end, as a new family of SARS-CoV-2 variants—nicknamed “FLiRT” variants—begins to spread nationwide.

These variants are distant Omicron relatives that spun out from JN.1, the variant behind the surge in cases this past winter. They’ve been dubbed “FLiRT” variants based on the technical names for their mutations, one of which includes the letters “F” and “L,” and another of which includes the letters “R” and “T.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Within the FLiRT family, one variant in particular has risen to prominence: KP.2, which accounted for about 25% of new sequenced cases during the two weeks ending Apr. 27, according to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Other FLiRT variants, including KP.1.1, have not become as widespread in the U.S. yet.

Researchers are still learning about the FLiRT variants, and many questions remain about how quickly they’ll spread, whether they’ll cause disease that’s more or less severe than what we’ve seen previously, and how well vaccines will stand up to them. Here’s what we know so far.

Is another COVID-19 wave coming?

Despite KP.2’s rise in the U.S., it’s too soon to tell whether the FLiRT family will be responsible for a major surge in cases, says Dr. Eric Topol, executive vice president at Scripps Research, who wrote about the FLiRT variants in a recent edition of his newsletter. For now, the amount of SARS-CoV-2 virus in U.S. wastewater remains “minimal,” according to the CDC, and hospitalizations and deaths have also continued to decline steadily since their recent peaks in January. At the global level, case counts rose from early to mid-April, but remain far lower than they were a few months ago.

KP.2 and its relatives will likely cause an uptick in cases, but “my hunch is it won’t be a big wave,” Topol says. “It might be a ‘wavelet.’” That’s because people who were recently infected by the JN.1 variant seem to have some protection against reinfection, Topol says, and the virus hasn’t mutated enough to become wildly different from previous strains. A recent study from researchers in Japan, which was posted online before being peer-reviewed, also found that KP.2 is less infectious than JN.1.

Do vaccines protect against KP.2 and other FLiRT variants?

Vaccines still provide good protection against COVID-19-related hospitalization and death. But two preliminary studies—the one from Japan and another from researchers in China, which was also posted online before being peer-reviewed—suggest the FLiRT variants may be better at dodging immune protection from vaccines than JN.1 was.

“That isn’t good,” Topol says, especially since many people who got the most recent booster—roughly 30% of adults in the U.S.— got it last fall, meaning their protection has begun to wane.

In an Apr. 26 statement, the World Health Organization recommended basing future vaccine formulations on the JN.1 lineage, since it seems the virus will continue to evolve from that variant. The most recent booster was based on an older strain, XBB.1.5.

How can I stay safe from new COVID-19 variants?

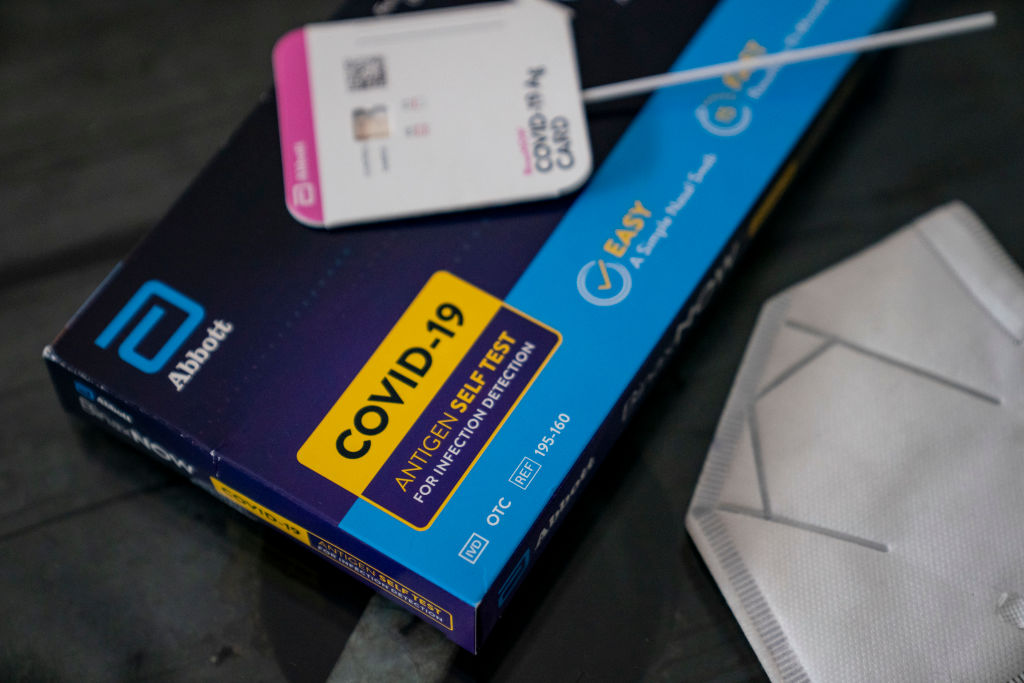

The virus continues to evolve, but public-health advice remains the same: stay up-to-date on vaccines, test before gatherings, stay home when you’re ill, and consider masking and avoiding crowded indoor areas, especially when lots of COVID-19 is going around.

Get the latest work and career updates delivered straight to your inbox by subscribing to our magazine category today. Stay informed and ahead of the game with Subscrb.

The content on this website has been curated from various sources and is for informational purposes only. We do not claim ownership of any of the content posted here, all rights belong to their respective authors. While we make every effort to ensure that the information is accurate and up-to-date, we cannot guarantee its completeness or accuracy. Any opinions or views expressed on this website are solely those of the original authors and do not necessarily represent our own. We do not endorse or take responsibility for the content or actions of external websites or individuals linked from this website. Any reliance on the information provided on this website is done at your own risk. Please note that this article was originally seen on the source website TIME, by the author Jamie Ducharme

-

SALE!

Forbes Asia Magazine Subscription

From: RM220 / year -

SALE!

Fortune Magazine Subscription

From: RM118 / year -

OUT OF STOCK

The Economist Magazine Subscription

From: RM1530 / year -

Inc. Magazine Magazine Subscription

From: RM22 / year -

Consumer Reports Magazine Subscription

From: RM22 / year -

Harvard Business Review Magazine Subscription

From: RM83 / month -

Entrepreneur’s Startups Magazine Subscription

From: RM4 / year -

BILLIONAIRE Magazine Subscription

From: RM131 / year